4 Critical Appraisal

EBM Explained. Sketchy EBM (2015). https://tinyurl.com/yyrrlqq9

As health professionals and researchers, we have a duty to make recommendations and decisions based on evidence, not beliefs. The term “evidence-based” first came into use in the 1990s, nearly two decades after Archie Cochrane, the namesake of the Cochrane Reviews, wrote the book “Effectiveness and Efficiency” and pointed to the need for the medical field to learn from the highest quality studies. This struck a chord with the profession, and medical schools began teaching their students evidence-based medicine (EBM), defined by Sackett et al. (1996) as:

The conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.

Since then, evidence-based medicine has expanded to evidence-based practice (or EBP) more generally, as well as to population-level approaches such as evidence-based public health (Brownson, Fielding, and Maylahn 2009) and evidence-based global health policy (Yamey and Feachem 2011).

The name “evidence-based medicine” is credited to Gordon Guyatt after the name “scientific medicine” was rejected (Smith and Rennie 2014). Visit ebm.jamanetwork.com/ to watch an oral history of evidence-based medicine.

This focus on evidence has saved countless lives and improved health around the globe. But how does data become evidence? Each year a few million new articles enter the scientific literature (Ware and Mabe 2015). Who determines what should be published and which studies should be designated as “high quality” evidence?

Well, we do. As scientists and researchers, we review manuscripts from our colleagues prior to publication, comment on articles once they appear in print, prepare systematic reviews and meta-analyses of published work, and sometimes attempt to replicate published findings in new studies. Broadly speaking, this process is known as critical appraisal, and it’s the focus of this chapter.

4.1 Getting started with critical appraisal

It feels daunting to critically appraise someone else’s work when you’re starting out in research. I find that students default to providing the type of feedback that feels most comfortable: spelling and grammar. Your colleague might appreciate this type of feedback, but copyediting is not critical appraisal, nor is it the core function of peer review. Yes, we need to help each other become better communicators of our ideas, but not at the expense of providing a critical review of the science.

So how do you approach the task of critical appraisal when you’re still building your foundation in research? Checklists!

](images/stard.png) Figure 4.1: STARD guidelines for diagnostic studies, www.equator-network.org

Figure 4.1: STARD guidelines for diagnostic studies, www.equator-network.org

One type of checklist is a set of reporting guidelines specific to the research design used in the study. You can find every reporting guideline on the website of the Equator Network, which stands for Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. Reviewing a randomized controlled trial? Check out the CONSORT guidelines. Diagnostic validity study? Try the STARD guidelines.

Pro tip: Include a completed checklist as an appendix when you submit manuscripts for publication. It helps reviewers do their job and sends a good signal about your attention to detail.

These guidelines are important because they represent the consensus of the scientific community regarding the essential details that a reader needs to evaluate a manuscript, organize a replication attempt, and include the study in a systematic review or meta-analysis. When you’re writing a manuscript, use the guidelines to make an outline that includes each piece of information. When you’re reviewing a manuscript, use the guidelines to confirm that the authors provided a full accounting of their study.

Systematic reviews are a great source for examples of critical appraisal because a systematic review is a critical appraisal.

If you find that the manuscript is lacking key details recommended by the reporting guidelines, you can enumerate these omissions for the authors and suggest that they follow [INSERT GUIDELINE NAME] to give the reader enough information to evaluate the work. This approach is useful even if you’re reading a published article and want to decide whether the evidence presented is of high quality.

4.2 The anatomy of a scientific paper

How I read a paper! Sketchy EBM (2015). https://tinyurl.com/y3n7vc7m

A scientific paper consists of four parts:

- An introduction that frames the research question

- A set of methodologies and a description of data

- A set of results

- A set of claims

Let’s consider what to think about when you read each section.

INTRODUCTION SECTION

A good Introduction explains the aim of the paper and puts the research question in context. In public health and medicine, this section is typically very short compared to the introductions in other disciplines like economics.

- Does the Introduction identify a gap in the literature that this paper will fill?

- Do the authors cite relevant literature? Does it appear that the authors have accounted for recent developments in the field?

- Is the research question clearly stated?

- Do the authors specify the aims of the paper?

We’ll consider research questions and aims in Chapter 5.

4.2.1 METHOD SECTION

A good Method section provides enough information to enable a reader to replicate the findings in a new study. Journal space constraints make this challenging, so authors often post supplemental materials online that provide additional details.

Review recent issues of the journal and consult the appropriate reporting guidelines to create an outline with subheadings that can guide your writing and reviewing.

The organization of the Method section varies by discipline and journal, but generally it includes some information about the research design, intervention (if appropriate), sample, materials or measures, data sources and procedures, and analysis strategy.

Can the study design answer the research question?

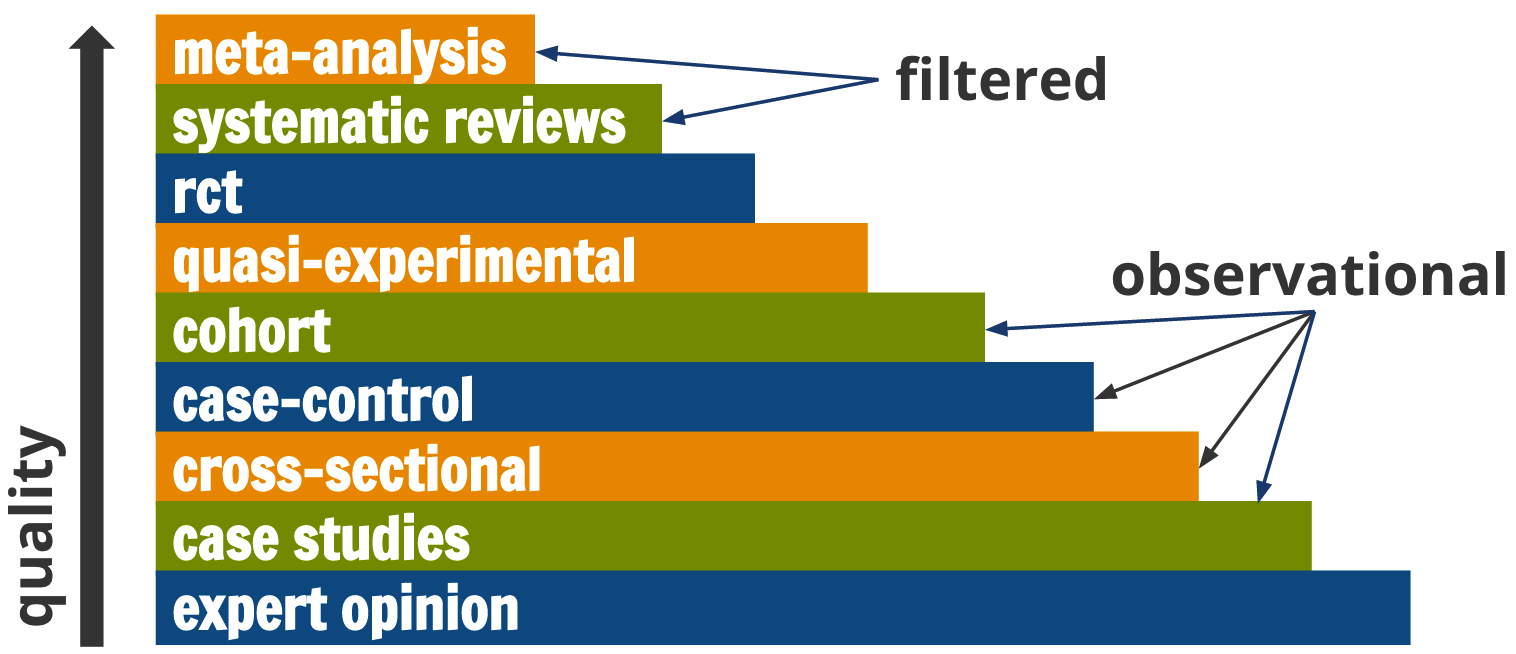

There are many different designs that can potentially answer most research questions, but not all designs are created equal. A graphic like Figure 4.2 is commonly used in the evidence-based medicine literature to convey this point. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews are ‘studies of studies’, and they sit atop the evidence hierarchy. They enjoy this status because they synthesize the best available evidence. No one study is the final word on a research question, so it makes sense that a meta-analysis that pools results and accounts for variable study quality could potentially provide a better answer than any one study alone.

Figure 4.2: Levels of evidence

However, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (2011) cautions researchers to pay attention to design features (e.g., how participants were selected) rather than labels (e.g., cohort study) because labels are broad categories. Therefore, this hierarchy is not absolute; these rankings reflect ideals. For example, RCTs can be poorly designed or poorly implemented, and the evidence from such a flawed study is not necessarily better than the evidence from a nonrandomized study just because it carries the label “randomized.” I’ll describe the logic and assumptions of common designs in Chapters 9 through 11.

How were participants selected and recruited?

I focus on ‘human subjects research’ in this book, but sampling is also an important topic in research not involving people.

Sidebar: How should you refer to the humans who participate in your studies? Is it ok to call these humans “people” or “participants”? Sure. They are people. I use “participants” most of the time. Others prefer “volunteers”. Few insist on “subjects”, with the notable exception of US federal regulations governing research.

We can’t collect data from every person in our population of interest (unless we define our population very narrowly, e.g., “authors of textbooks named Eric Green”), so we have to sample a subset of people from the population. For instance, let’s say that we want to know what eligible voters in the US think of a certain presidential candidate. There were roughly 160 million people registered to vote in the 2018 US presidential election. We can’t contact all 160 million, so imagine we survey 1000 registered voters, or 0.000006% of the population. The details around who these people are and how they got into our study matter for our inferences. Can these 1,000 people represent all US voters? To answer this question for the reader, we have to describe sample selection and recruitment in the Method section.

- What made someone eligible or ineligible to participate? Who was excluded, intentionally or not?

- How were participants selected and invited to participate?

- Was this selection process random, or did the researchers invite participants based on availability?

- How many were invited, and how many accepted the invitation?

- Who refused the invitation to participate, and how are they different from the people who accepted?

We’ll revisit sampling and sample size in Chapters 12 and 13.

What materials and/or measures were used?

Almost every study uses some type of materials or measures. Diagnostic studies, for instance, evaluate a diagnostic test or a piece of hardware that analyzes the test samples. Environmental studies often use sophisticated instruments to take atmospheric measurements. Studies like these always provide specific details in the Method section about the materials and equipment used.

Study variables also need to be precisely defined in the Method section. For instance, hyperparasitemia describes a condition of many malaria parasites in the blood. But what constitutes “many”? The World Health Organization (WHO) defines it as “a parasite density > 4% (~200,000/µL)” (WHO 2015b). A manuscript should be precise with respect to how measurement is operationalized.

This holds for studies measuring social or psychological constructs. For instance, in a study of anxiety, a definition of the concept of “anxiety” should be provided. Is an anxiety disorder diagnosed by a psychiatrist? If so, what is the basis for this diagnosis? Or is anxiety inferred from a participant’s self-reported symptoms on a checklist or screening instrument? If so, what are the questions and how is the instrument scored?

We’ll tackle issues of measurement, including study outcomes and indicators, in Chapter 7.

How was the study conducted and how were the data collected?

The Method section should also describe what happened after participants were recruited and enrolled.

- What happened first, second, third?

- Who collected the data, and how were they trained?

- For intervention studies, the data collection procedures should describe how participants were randomized to study arms and what happened (or did not happen) in each arm.

- Were the participants, data collectors, and/or patients blind to the treatment assignment?

We’ll discuss data collection methods in Chapters 14 and 15.

How were the data analyzed?

In this section authors typically describe the approach and logic of the core analysis. In an economics paper, this might be called the empirical strategy.

- If analyzing qualitative data, what is the analysis method? Common methods include content analysis, narrative analysis, discourse analysis, and grounded theory.

- If analyzing quantitative data, is the statistical/econometric model described clearly?

- What are the assumptions of the analysis?

Was the study approved by an ethics board?

The US Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (i.e., the “Common Rule”) defines research as “a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge…” If the research involves human subjects, it must be reviewed and approved by an institutional review board (IRB) before any subjects can be enrolled. Most studies fall under IRB oversight, but some, such as retrospective studies or quality control interventions, may qualify as exempt.

Increasingly, researchers are taking the additional step of registering their study protocol prior to the study launch in a study clearinghouse like https://clinicaltrials.gov/. This registration is a requirement for drug investigations regulated by the FDA, and it’s expected by many journals. Preregistration does not ensure trustworthy results, but the practice fosters a welcome increase in research transparency. If the analysis described in an article deviates from the planned analysis, the authors are expected to provide a compelling justification. We will return to pre-registration and open science more generally in Chapter 18.

4.2.2 RESULTS SECTION

Can each finding be linked to data and procedures presented in the Method section?

Every finding in the Results section should be linked to a methodology and source of data documented in the Method section. Articles in medical journals are some of the shortest, so supplemental materials posted online may be needed to obtain a clearer sense of what the authors did and found.

Is the analysis correct?

This is a hard question to answer during critical appraisal. Most of the time (at least in public health and medicine) you do not have access to the data and analysis code, so you cannot verify that the analysis is correct. You have to base your assessment on the authors’ written description of the data and analysis.

Even if you did have access to materials to reproduce the analysis, some analyses are so complex that only people with extensive training feel qualified to question the accuracy of the results. When reviewing a study with complex analyses, it may be necessary to consult with colleagues.

4.2.3 DISCUSSION SECTION

Is each claim linked to a finding presented in the Results?

Each claim should be supported by results that are reported in the paper. If there is no link between a claim in the Discussion section and a finding in the Results section, the authors may be “going beyond the data.” For example, if a manuscript presents data on the efficacy of a new treatment for malaria but does not include any data on cost, then it would be inappropriate to claim that the treatment is cost-effective. Although it’s legitimate to speculate a bit in the Discussion section based on documented findings, authors should be careful to label all speculation as such—and these hypothetical forays should never be included the article’s Abstract.

Is each claim justified?

Consider each claim in relation to the results presented to evaluate whether the authors’ arrived at the correct interpretation of the data presented. Did the authors come to a reasonable conclusion, or did they make conclusions that are not supported by the analysis? For instance, if the analysis provided only weak or mixed evidence that a new program is efficacious, it would be inappropriate to recommend scaling-up the program.

Are the claims generalizable?

One approach to promoting generalizability is to randomly sample participants from the population of interest. For example, Wanzira et al. (2016) analyzed data from the 2014 Uganda Malaria Indicator Survey, a large national survey, and found that women who knew that sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine is a medication used to prevent malaria during pregnancy had greater odds of taking at least two doses than women who did not have this knowledge. Because the UMIS is nationally representative, the results could apply to Ugandan women who did not participate in the study. Would the results be generalizable to women in Tanzania? An argument could be made that they would. Would the results be generalizable to women in France? No, probably not; among other things, malaria is not an issue there.

Just about every study is conducted on a narrowly constructed sample. Have you read a psychology paper recently? Chances are the sample was WEIRD: White, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. Most likely the participants came from the “undergraduate pool”—psychology majors willing to take part in the study for extra credit.

In global health, it’s common to read qualitative studies involving 20 patients who receive services from one rural primary healthcare facility—a handful of people from one small town in one small corner of a country of millions.

When we read these studies, we are not interested in the hyper-local story, per se (Shadish, Cook, and Campbell 2003). Instead, we want to know if the results can generalize to the broader target population. When a study is so highly localized that the results are unlikely to generalize to new people and places, we say that the study has low external validity.

I’ll tell you more about generalizability and external validity in Chapter 12.

Are the claims put in context?

A good Discussion section puts the study findings in context by telling the reader how the study adds to the existing literature.

- Do the results replicate or support other work?

- Or do the findings run contrary to other published studies? What are some ideas about why this might be?

- How does the study advance our knowledge or fill gaps in the literature?

What are the limitations?

No study is perfect, so it’s customary to include a paragraph or two outlining the shortcomings. Such limitations span all aspects of the study design and methods, from sample size to generalizability of results, to data validity and approaches to statistical analysis. Communicating shortcomings can provide a valuable resource for future researchers in terms of caveats and research directions.

4.3 Communicating your critical appraisal

The following steps can apply to critical appraisals that you do not intend to share with the authors, such as an annotated bibliography to guide your own work.

When you’re asked to review a manuscript for a journal or a grant proposal for a funder, there is an expectation that you will communicate your feedback in written form. We will dive into peer review and the publishing process in Chapter 19, but I want to use the remaining part of this chapter to discuss tips for communicating your critical appraisal.

STEP 0: DON’T BE A JERK

It’s easy to tear down someone else’s work. It’s much harder to give constructive feedback that will help make this work better. This is not to say that you should give a pass to poorly conducted research or confusing or incomplete write-ups. The point of critical appraisal is to share critical feedback. But feedback that focuses on someone’s perceived failings as a person or scientist are out of bounds. If you receive such feedback, try to remember that you’re not your work and this type of feedback is lazy and unprofessional. If you’re learning from a mentor who is lazy and unprofessional, find new opportunities for mentorship.

Don’t be a jerk.

“I don’t see how your approach has potential to shed light on a question that anyone might have.” pic.twitter.com/jgWrKaKlGG

— ShitMyReviewersSay ((???)) March 11, 2019

It’s not hard to avoid insulting language. Here are a few examples from PLOS:

| When you want to say | Say this instead |

|---|---|

| The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic. | The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al. |

| The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it. | While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text. |

| It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake. | The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. |

| The manuscript is fatally flawed. | The study does not appear to be sound. |

| The writing is terrible. | The authors should revise the language to improve readability. |

STEP 1: READ TO UNDERSTAND THE AIMS

Stiller-Reeve (2018) published tips for peer review and a handy workflow. His suggestion is to read the paper several times with a different objective each time.

On your first pass, read to get an overview of the article and to understand what the authors set out to do. In your own words, write a paragraph that expresses your understanding of the study’s aims and objectives. What do you understand the paper to be about, and what is your perception of the potential contribution?

If the peer review system is working, however, this should be rare. Journal editors and grant funders conduct initial screenings and can reject such papers without sending them out for review. So before you throw in the towel and claim to have found fatal flaw, take the time to understand the paper’s aims and approach.

Sometimes you will read a manuscript with one or more fatal flaws that no amount of constructive criticism will help. To be clear, fatal flaws are about the science, not the writing. Unclear writing can be fixed. Bad science cannot.

For instance, if the aim of the study is to estimate the national prevalence of disease in Uganda and the study is limited to a convenience sample of patients who sought care at a particular health clinic, this would be a fatal flaw. This study design cannot answer the question the authors set out to answer. When this happens, it’s OK to describe this fatal flaw and recommend that the paper be rejected or the grant not be funded. You do not have to continue spending time on a manuscript that is dead on arrival.

STEP 2: DIG INTO THE DETAILS

If there are no fatal flaws, read the paper again to understand the details of the scientific approach: sampling, measurement, procedures, intervention, analysis. Find the appropriate reporting guidelines from the Equator Network and use the questions above to go through each section of the paper to determine whether the authors describe the study in sufficient detail.

STEP 3: CONSIDER THE CONCLUSIONS

On your third pass, use your understanding of the details presented in the Method and Results sections to think critically about the authors’ conclusions. Do you have the same interpretations of the data?

STEP 4: WRITE YOUR REPORT

Summary paragraph

Your report should begin with the paragraph you wrote in Step 1 that conveys your understanding of the aims and potential contribution of the paper. This paragraph should end with your overall recommendation. Should the paper or proposal be published or funded? Revised? Rejected?

In this case the reviewer went on to answer his or her question in the negative. Nevertheless, it was a constructive review, even if we were disappointed in the outcome. We later published a revised version in a different journal (Blattman et al. 2016).

Here is an example of a summary paragraph from a review of a paper I co-authored that was not accepted at the first journal.

The authors conduct a field experiment in rural northern Uganda to estimate the effect of cash grants, training, supervision of grant use, and incentives to form social groups on the entry into self employment, and labor market earnings. Residents of 120 villages and an NGO identify 10 to 15 of the poorest individuals to participate in the program. The majority of the participants (86 percent) are female. At baseline, participants have cash earnings of only about $2 per week. The experiment is a ‘randomized wait-list’ design, with 60 villages selected for immediate treatment. The remaining 60 receive treatment about 20 months later. Treatment is a cash grant of $150, plus five days of business training leading to a simple plan for a new business. Most recipients also receive five follow-up visits intended to encourage them to invest the grant in a business and to provide advice on the business. The authors find that the grants, training and follow-up treatment has a large and significant effect on running a non farm business, doubling the baseline rate of around 40 percent for women. Cash earnings of women (men) increased by 92 (74) percent. The experiment is well designed and executed, and the paper is well written. The paper clearly should be published in a good journal. The question is whether it rises to the level of [this journal].

Major concerns and minor comments

The rest of the report should support your overall recommendation. It’s customary to divide your comments into two sections: (1) Major concerns and (2) Minor comments. If you’re recommending that the manuscript or proposal be revised, major concerns are issues that the authors must explain or remedy to get your endorsement for publication or funding. Maybe you’re unclear about the sampling strategy as described and, therefore, you cannot make an overall determination about the validity of the results. Or maybe you feel that the analysis method is flawed, suboptimal, or incomplete. Major concerns get at the veracity of the science and conclusions.

Minor concerns, on the other hand, include issues that you believe detract from the paper’s potential, but do not represent core matters of science. You do not need to copyedit the draft, but you might include suggestions for improving the readability of the paper under minor concerns. Likewise, you might offer additional references the authors could consider adding to provide more context for the results. When you’re writing minor concerns, you’re offering ideas for how to make the paper better.

4.4 The Takeaway

Critical appraisal is an important part of the scientific process. It’s what we do when asked to review a manuscript prior to publication, evaluate a grant proposal, read a new paper published in our field, and prepare a systematic review or meta-analysis. You might feel unprepared to provide critical feedback on someone else’s work until you know more about research methods, designs, and analysis, but it’s easy to get started if you use a framework like the reporting guidelines published by the Equator Network or some of the tools listed below in additional resources. When it’s time to communicate your feedback, be nice. Be critical, be honest about the flaws you perceive, but always be nice and assume that the authors did their best. If their best is not publishable and cannot be fixed with revision, then recommend that the paper be rejected or the grant not funded. It happens. Even in rejecting someone’s work you can offer ideas for improvement. It’s common to structure your feedback according to the major concerns you see, followed by minor comments that could improve the accuracy or clarity of the paper.

Don’t be this reviewer:

‘This reads like a pretty good MA level seminar paper but comes nowhere near the intellectual status required for publication in journal X’ pic.twitter.com/FCZmsaB6kb

— ShitMyReviewersSay ((???)) February 11, 2019

Additional Resources

Critical appraisal worksheets from the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine

BMJ Series on “How to Read a Paper”

Critical appraisal resources from Duke Medicine

Page built: 2020-08-09